“If you build it, they will come” doesn’t always apply to oyster reef restoration.

Oysters are picky and there are several Goldilocks conditions they like to be just right – not too salty, not too fresh, not too hot, not too muddy, and the list goes on. A suite of environmental parameters, such as temperature, salinity, and dissolved oxygen, were used by researchers at The Nature Conservancy to develop an Oyster Habitat Suitability Model (HSM) for the Pensacola Bay System (PBS). This model will help us to identify locations for oyster restoration projects that give oysters the best possible chance of survival.

However, even with all this information at our fingertips, the success of oyster restoration projects can still be limited without the presence of larval oysters in the water to colonize new reefs. So how do we know where larval oysters are?

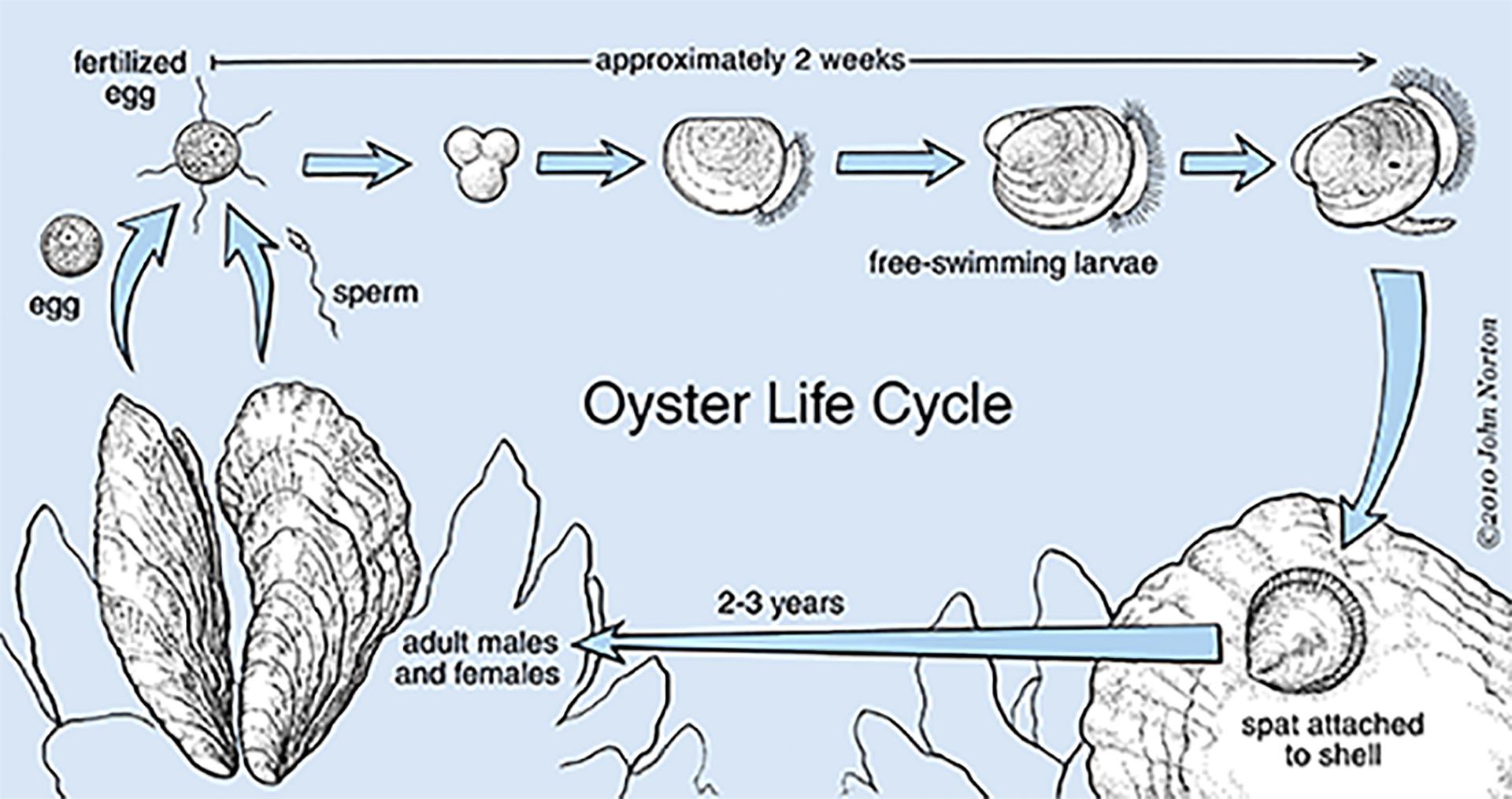

Oysters reproduce by spawning larval oysters into the water. These tiny, larval oysters need a hard surface to settle on, such as oyster shells! Once they settle onto a surface they are referred to as spat. Researchers can determine juvenile oyster recruitment by deploying standardized devices and counting the number of spat that settle on the device after a certain time frame.

We joined FWC Fish and Wildlife Research Institute researchers from the Apalachicola Field Laboratory in March to track down larval oysters in the (PBS). The chilly, foggy morning was a good reminder that March is typically a bit early for oyster spawning in our area. Though we don’t expect to see much spat after the first month, it is ideal to begin monitoring before the expected spawning season to ensure we capture the full recruitment window. Afterall, oysters don’t follow calendar dates and shifting environmental conditions could allow for spawning to occur earlier than expected.

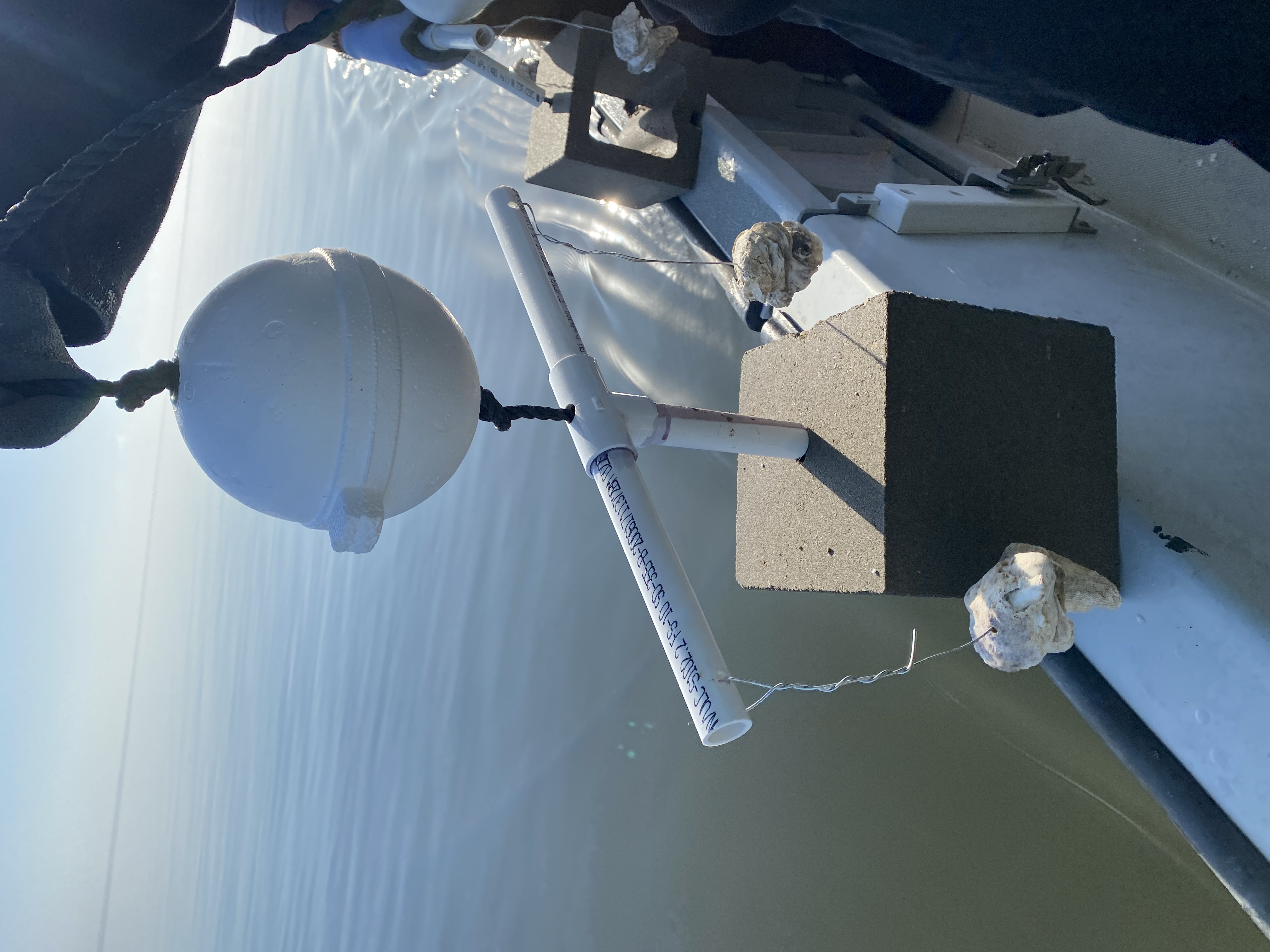

Floating spat monitoring arrays were deployed at multiple locations across Escambia and East Bays. The arrays consisted of PVC t-trees with floats attached above and a cement block attached below. Two oyster stringers (wires strung with a set number of oyster shells) were attached to each end arm of the t-tree. As we arrived at each site, we quickly assembled each array in a flurry of tying, stringing, and twisting to secure the cement blocks, buoys, PVC t-trees, and oyster stringers together. At the same time, we collected site and water quality data. Then, three of the newly assembled floating t-trees (that make up one array) were dropped off the side of the boat in series as our captain steered us forward.

After being deployed for a month, the spat stringers will be collected and processed to determine the number of spat on each shell. Fresh oyster stringers will be added to each unit, and the floating t-trees will be returned to the water. These arrays will be checked monthly through the fall.

The FWRI team will also deploy sediment traps to quantify sediment loading rates at selected sites throughout the PBS. Oyster spat need a solid substrate to settle on, something that is in short supply in the PBS compared to historical records. A major contributing factor to this decline is layers of sediment and muck that has smothered oyster reefs and turned some sandy bottom substrates to mud. Stay tuned for muddy updates from the field updates on this sediment monitoring effort!

This FWRI led research is a Florida Trustee Implementation Group (FL-TIG) project funded through Deepwater Horizon funds. These two monitoring efforts are another piece to the complicated puzzle that is oyster restoration, helping to ensure the best possible odds that when we build it, they will come.